The Montaukett Indian Nation, an indigenous people of Long Island, is awaiting the final decision from the governor’s office as to whether the tribe can officially regain its New York State recognition, which had been stripped away during a legal battle in 1910.

This year’s bill seeks to overturn the 1910 ruling and was introduced by New York State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr. (D-NY) and New York State Sen. Anthony Palumbo (R-NY). This is the fifth time the bill has been passed by both houses of the New York State legislature, only to be vetoed by Gov. Kathy Hochul and former Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

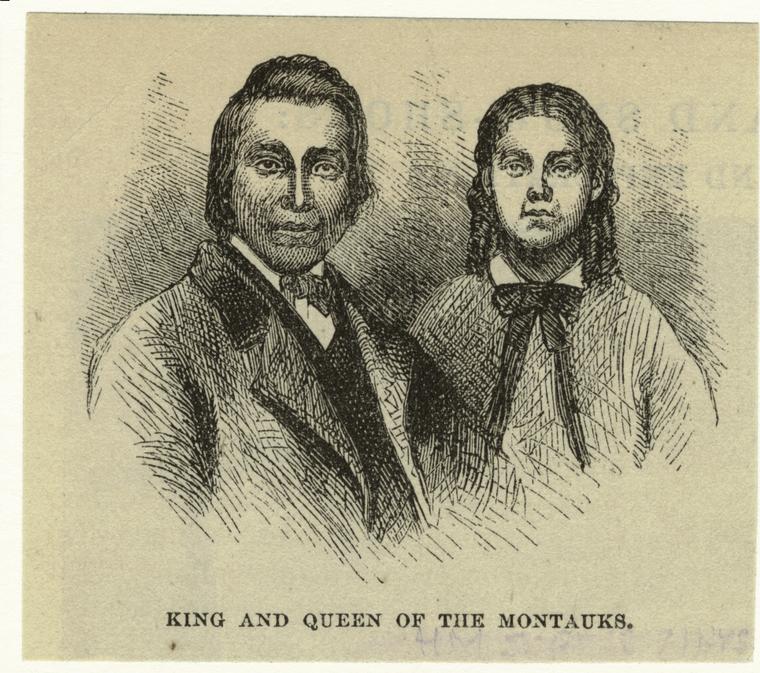

Robert Pharaoh is the current Chief of the Montaukett Indian Nation and a direct descendant of Wyandank Pharoah, the Montaukett leader during the 1900s. NBC New York spoke with Robert Pharaoh during the 77th annual Shinnecock Powwow held on the Shinnecock Indian Territory in Southampton, New York.

Pharaoh does not believe the bill will be signed into law this time and points fingers at local and federal politicians.

“It’s not the local community that’s against it. It’s the politicians because they’re all bought and paid for. Everybody now is learning what I found out a long time ago. They’re all too busy stuffing their pockets and smiling,” Chief Pharaoh told NBC New York, who later continued, “The only time that they come out of the woodwork to make it look like they actually want to do something for you is election time.”

Pharaoh continued to note during the interview that the root of the problem likely ties back to particular donor contributions within each of the governors’ campaigns.

NBC New York reached out to Gov. Kathy Hochul as to the reasoning behind her decision last year, and the administration referred back to the veto letter stating that “New York has historically only recognized Tribes and Nations that have had a continuous government-to-government relationship with New York since the State was established.”

NBC also reached out to former Gov. Andrew Cuomo who vetoed the four previous attempts made by the Montauketts. A spokesperson responded referencing the administration needing more information from the tribe.

The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs did not have anything specific to share at this time, while the New York Office of Indian Affairs did not respond for comment.

Montaukett History

Dating back to 1906, the Pharaoh v. Benson case was one of three land claim lawsuits that fought over the rights of about 4,200 acres to expand the Long Island Railroad to Montauk, New York.

Before 1910, the Montaukett tribe had been recognized by the U.S. government and New York State. When the case was presented, Arthur W. Benson, president of Brooklyn Gas Light and investor in building the Brooklyn Bridge, wished to further develop eastern Long Island envisioning “a playground for the rich,” according to Katherine Sorrell, an attorney with Cultural Heritage Partners.

Allison McGovern is an anthropological archeologist in the greater New York City area who has worked with the Montauketts since 2015, particularly studying the East Hampton George and Sara Fowler family house, a Montaukett home dating from the 1880s to 1980s.

Through her historical research, McGovern uncovered what the Montaukett life and identity were in a more recent past during the 20th century moving past colonialism. She notes that colonialism and the forced adaptations in the Native American culture contribute to their so-called “disappearance” from society.

“Typically, in the past, archeologists would look at that material and say that indigenous people were losing their sense of identity. There’s a trope of cultural loss associated with the replacement of stone tools with modern utensils, like metal cut-ware or European manufactured ceramics, and that plays completely into this idea that the Montauketts vanished,” McGovern told NBC 4.

McGovern learned that there is a serious disconnect in archaeology and anthropology that played a part in tearing the indigenous past from the present, which connects back to the legal troubles today.

“It goes back to that case in 1910, and it’s the fight for renewal of that recognition has been going on for now, 113, almost 114 years,” said Sorrell, an attorney representing the Montaukett Indian Nation in their latest fight to reclaim their recognition.

Sorrell labels the case as blatant racism and “the denial of the inherent rights that the Montaukett Indian Nation had at the time.”

“You had a dispute between the Montauketts and an underhanded land developer who wanted to build a playground for the rich accessible by rail from Manhattan. He, unfortunately, won the case. The judges, in both the Supreme Court case decision and in the appeals decision, both used racist — blatantly racist — language against the Montauketts,” said Sorrell.

The 1910 decision declared the tribe to be extinct despite the active Montaukett members standing in the courtroom and continued use of their ancestral land. The ruling denied the tribe’s enduring presence on Long Island since the English and Dutch colonists arrived in the 1600s.

The overt racism used in the case was apparent throughout, according to Executive Director of the Montaukett Indian Nation Sandi Brewster-Walker, who described how hundreds of Montauketts were present in the courtroom to hear the verdict.

“With 300 and some people in the room, they went through and declared us non-existent,” Brewster-Walker said to News 4, “A lot of the names in the court case are of people in the room. They just took an eraser and erased us. That’s our ‘trail of tears.'”

They just took an eraser and erased us. That’s our ‘trail of tears.’

Sandi Brewster-Walker, Executive Director of the Montaukett Indian Nation

According to Brewster-Walker, there are about 1,200 Montauketts, ages 18 and older, residing on Long Island. Due to the past process of census counts in the late 1700s, the specific number is hard to pinpoint.

“All you have to look is the U.S. Census 1790 and start following the instructions that were given to the numerators,” Brewster-Walker said. “The numerators were told to determine the person’s race by the color of their skin. We never looked white, most of us. For quite a few years it stated, ‘If you are Indian or white, then you’re considered Indian. If you’re Indian and you have brown skin, you’re not considered Indian.”

Brewster-Walker explained that if a person at that time had brown skin, they were described as Black, African or other terms on the census.

It is this erasure that the Montaukett Indian Nation is fighting to undo. According to Christopher Matthews, professor and chairperson of the anthropology department of Montclair State University in New Jersey, it is a disservice to silence Native American communities. He says, that while advocacy is appreciated, the most important action is to listen as the tribe tells its own story.

“I think the best thing to do is to let their voices be heard,” Matthews said to NBC during an interview at the Montclair State University lab. “The members of this community are there. My voice can’t replace any Native voice. Letting a community that’s in the process of trying to gain recognition tell that story.”

Legal Steps for Recognition

Over the years, the Montauketts have restructured the bill to bring back state recognition, uncovering more information from their past. The tribe is now awaiting a “yes or no” from the governor’s office — for a fifth time.

Pharaoh is not anticipating a forward-moving response, but Brewster-Walker tends to disagree.

“I think it will pass this time,” Brewster-Walker said. “If it doesn’t, we are still going to keep trying. And, then, if it doesn’t pass, we’ll make the decision about suing,” noted Brewster-Walker.

Sorrell and Werkheimer are optimistic that the fifth time is the charm.

“I would just emphasize that the historical record speaks for itself, as does the broad support that the Montauketts have among both sides of the aisle and the state legislature,” Sorrell said, stressing the local bipartisan support politicians have shown the Montaukett Indian Nation in their journey to regain their recognition, despite the various efforts stalling once the bills reach the governor’s desk for signature.

Additionally, aside from working on their state recognition, the Montaukett Indian Nation is trying a different avenue and simultaneously working to gain federal recognition, which the tribe had attempted previously.

Obtaining recognition on the state and federal levels are not the same and separate processes.

Federal recognition is considered the “gold standard” to Matthews, who notes that this showcases “a relationship that says, ‘They [Natives] reside within our country, they don’t have necessarily their own political boundaries,’ so sometimes reservations can work that way because you are on or off Indian land.”

The federal recognition falls into the tribe’s self-determination and sovereignty comes with it.

A state-recognized tribe does not have a centralized government and does not have the right to assert themselves to even the state government that way, says Matthews.

“It is a decision by the state to recognize their indigenous heritage and to celebrate that, but it doesn’t give that community much in the way of political autonomy,” Matthews said.

There are three ways a tribe may get federal recognition: through a specific act of Congress through a piece of legislation; through a process with the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs; or a decision by the federal court.

In New York, there are eight federal and nine state-recognized nations, while Connecticut has two federal and five state-recognized tribes, and New Jersey has three state-recognized tribes. The path to recognition tends to be long, arduous, and oftentimes costly, according to Matthews.

The traditional route for federal recognition is through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a process that requires reams of documentation proving the existence of an indigenous community without break since colonization.

“The process can take years because you have to assemble this information in addition to living your life. You’re not given resources to do this research. You’re not given external support to help you do this. You have to either raise grant money to hire someone to help you or you have to try and do it yourself,” noted Matthews.

Greg Werkheiser, an attorney with Cultural Heritage Partners, the law firm representing the Montaukett Indian Nation in their latest attempt to regain recognition, echoed the same, further saying the process can take upwards of decades.

“There was an estimate done a number of years ago that it takes a tribe on average 30 years to get through the process,” Werkheiser said, adding that the minimum cost to go through the process for these tribes can reach upwards of $10 million to $20 million.

Evidence that is requested from the tribes may be documentation that is hard to come by due to the history of Native Americans in this country, particularly if the government played a role in eliminating any information.

“I’ll offer you an example of the six Virginia tribes that were some of the first encountered by Europeans in the United States, and yet, were only federally recognized in 2018,” Werkheiser added.

When Pharaoh first worked on the state application, there were five Montaukett elders alive, all since have died, including his mother. The over 650-page submission took three years to complete, and he dedicated the work to her.

When asked why the Montaukett are still pushing for state recognition after numerous defeats, Brewster-Walker simply responded that this would close the case for their family.

“If you are recognized by New York State, if you don’t have health insurance, you can get health insurance. The [Indian] Child Welfare Act will benefit us, but I haven’t heard of a case where [a Native American] child is coming up to be adopted, they should be offered to an Indian family first. In the last 20, or 30 years, I haven’t heard of a case that involves us. Those are the only two benefits,” said Brewster-Walker.

The Indian Child Welfare Act, also known as ICWA, guides States when it comes to the handling of child abuse and adoption cases involving Native American children.

I just want our dignity back. I just want to get our recognition back.

Chief Robert Pharaoh, Montaukett Indian Nation

Pharaoh believes that not owning land could be hindering the Montaukett Indian Nation from regaining its recognition.

“If you have a piece of property or you’re on land or you’re on a reservation, they look at you a little bit different. You’re not as much of a threat because they’ll recognize, ‘OK, well, they’ve already got land so we don’t have to worry about them coming after land, so we’ll give them the recognition and we’ll give them the little things that the government throws your way,'” Pharaoh pointed out.

The economic development is important for the Montauketts and in discussion for access to empty federally or state-owned land to put towards a community center or official powwow ground for the tribe. For a casino to be built, a tribe must be federally recognized, not state-recognized.

“I just want to get our dignity back. I want to get our recognition back, and I want to get the federal and state government to admit that they were wrong and that they want to correct an injustice,” said Pharaoh.

This story uses functionality that may not work in our app. Click here to open the story in your web browser.

0 Comments